Acyclic Behavior Change Diagrams

Gjalt-Jorn Peters

2019-01-16

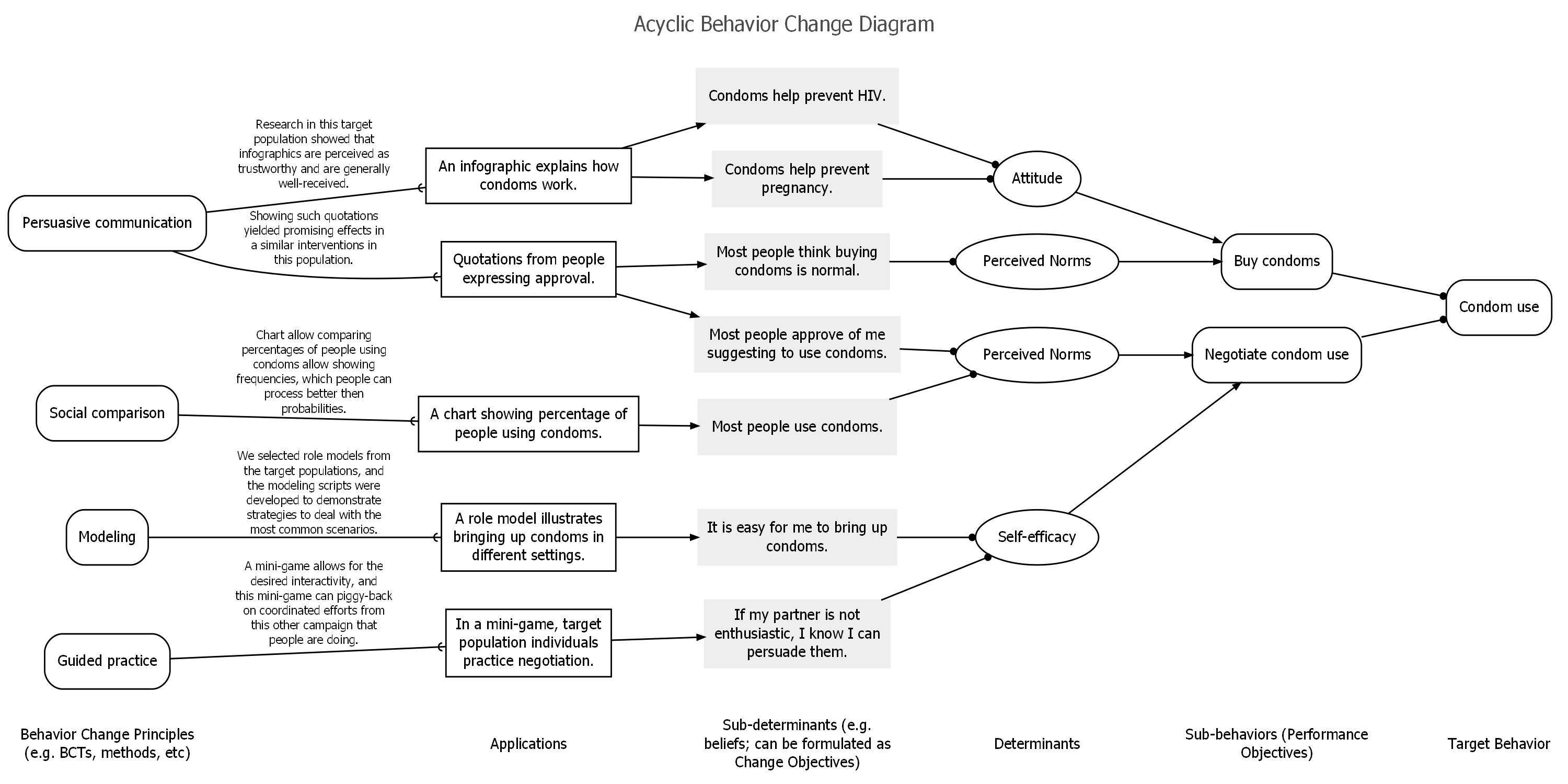

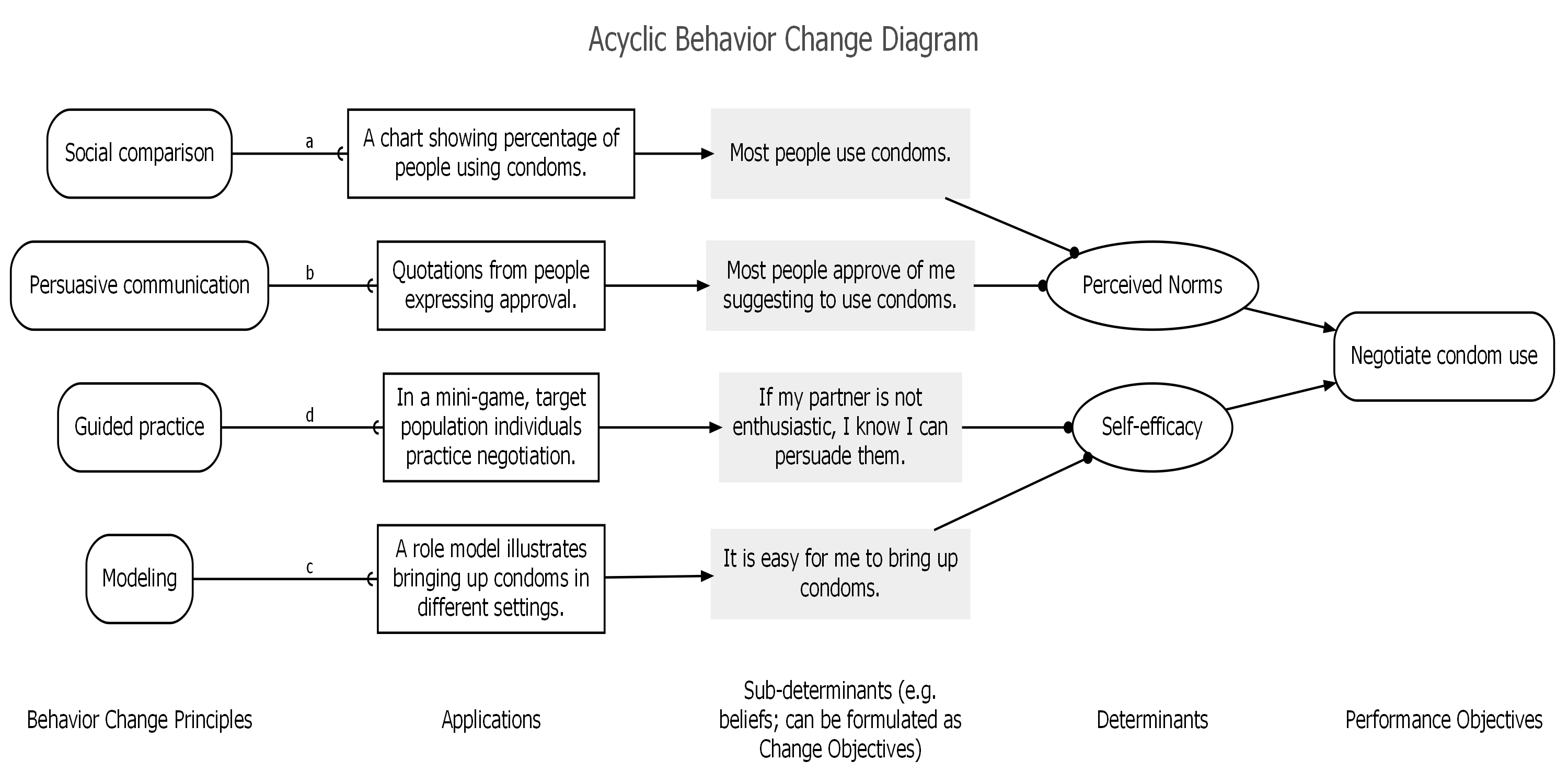

abcd.RmdAcyclic Behavior Change Diagrams (ABCDs) are diagrams that illustrate the logic model (also known as ‘theory of change’) underlying any intervention, treatment, or campaign aiming to change some aspect of people’s minds and/or behaviors. Specifically, the ABCD shows the assumed causal and structural assumptions, thereby showing what is assumed to cause what (e.g. which elements of the intervention are assumed to influence which aspects of the target population’s psychology?) and what is assumed to consist of what (e.g. which determinants are assumed to contain which specific aspects of the target population’s psychology?).

Such ABCDs are generated from a uniform, machine readable, format: a table, for example as stored in a comma separated values (CSV) file. In it most extensive form, the table has the following columns:

- Behavior Change Principles (BCPs): The specific psychological principles engaged to influence the relevant sub-determinants, usually selected using the determinants to which the sub-determinants ‘belong’. These are also known as methods of behavior change in the Intervention Mapping framework, or behavior change techniques, BCTs, in the Behavior Change Wheel approach. For a list of 99 BCPs, see Kok et al. (2016).

- Conditions for effectiveness: The conditions that need to be met for a Behavior Change Principle (BCP) to be effective. These conditions depend on the specific underlying Evolutionary Learning Processes (ELPs) that the BCP engages (Crutzen & Peters, 2018). If the conditions for effectiveness (called parameters for effectiveness in the Intervention Mapping framework) are not met, the method will likely not be effective, or at least, not achieve its maximum effectiveness.

- Applications: Since BCP’s describe aspects of human psychology in general, they are necessarily formulated on a generic level. Therefore, using them in an intervention requires translating them to the specific target population, culture, available means, and context. The result of this translation is the application of the BCP. Multiple BCPs can be combined into one application; and one BCP can be applied in multiple applications (see Kok, 2014).

- Sub-determinants: Behavior change interventions engage specific aspects of the human psychology (ideally, they specifically, target those aspects found most important in predicting the target behavior, as can be established with plots. These aspects are called sub-determinants (the Intervention Mapping framework references Change Objectives, which are sub-determinants formulated according to specific guidelines). In some theoretical traditions, sub-determinants are called beliefs.

- Determinants: The overarching psychological constructs that are defined as clusters of specific aspects of the human psychology that explain humans’ behavior (and are targeted by behavior change interventions). Psychological theories contain specific definitions of such determinants, and make statements about how they relate to each other and to human behavior. There are also theories (and exists empirical evidence) on how these determinants can be changed (i.e. BCPs), so althought the sub-determinants are what is targeted in an intervention, the selection of feasible BCPs requires knowing to which determinants those sub-determinants belong.

- Performance objectives: The specific sub-behaviors that often underlie (or make up) the ultimate target behavior. These are distinguished from the overarching target behavior because the relevant determinants of these sub-behaviors can be different: for example, the reasons why people do or do not buy condoms can be very different from the reasons why they do or do not carry condoms or why they do or do not negotiate condom use with a sexual partner.

- Behavior: The ultimate target behavior of the intervention, usually an umbrella that implicitly contains multiple performance objectives.

ABCDs can be generated using the [behaviorchange::abcd()] function in the behaviorchange R package.

They can also be generated from the online app that runs at https://a-bc.eu/apps/abcd.

Examples

This are two example ABCDs. The ABCD tables are included in the behaviorchange package, and the identical tables are available on Google Sheets.

A simple but complete ABCD

behaviorchange::abcd(behaviorchange::abcd_specs_complete);

A simple but complete ABCD

The ABCD table for this ABCD is available at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1U1j-VoiK3WmfveJ7VpUMY_H9WNXDh85a8jKbM67AQSI/edit#gid=0.

An ABCD with only one target behavior and no specified conditions

behaviorchange::abcd(behaviorchange::abcd_specs_single_po_without_conditions);

An ABCD with only one target behavior and no specified conditions

The ABCD table for this ABCD is available at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1o2w6Yt0Wyy8xVGTvwb_NRcba4B79pbnlYG3wh-qNhek/edit#gid=0.

References

Crutzen, R., & Peters, G.-J. Y. (2018). Evolutionary learning processes as the foundation for behaviour change. Health Psychology Review, 12(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2017.1362569

Peters, G.-J. Y., & Crutzen, R. (2017). Pragmatic nihilism: how a Theory of Nothing can help health psychology progress. Health Psychology Review, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2017.1284015

Kok, G. (2014). A practical guide to effective behavior change: How to apply theory- and evidence-based behavior change methods in an intervention. European Health Psychologist, 16(5), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/r78wh

Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., Peters, G.-J. Y., Mullen, P. D., Parcel, G. S., Ruiter, R. A. C., Fernández, M E., Markham, C., & Bartholomew, L. K. (2016). A taxonomy of behavior change methods: an Intervention Mapping approach. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155